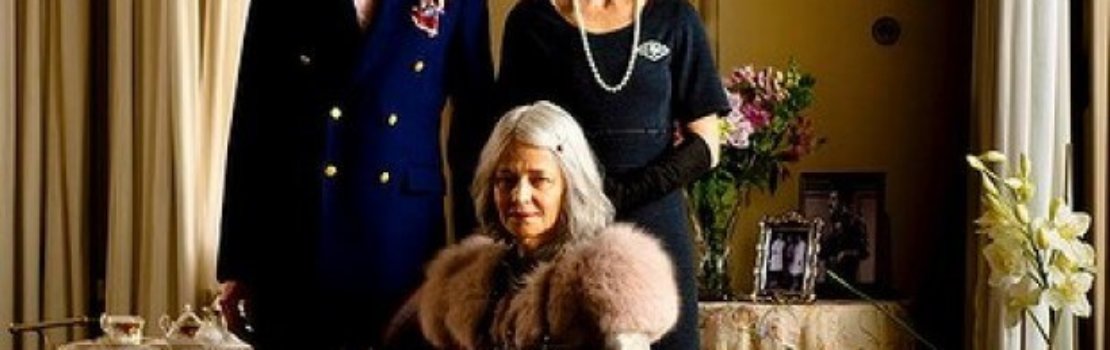

Sydney, 1973: As the wealthy and powerful Elizabeth Hunter (Rampling) approaches death, her unscrupulous children, Basil (Rush) and Dorothy (Davis) return to the family estate. Long alienated from a mother they barely knew, and themselves having fallen upon hard times, they scheme of ways to win her vast inheritance.

EYE OF THE STORM is director Fred Schepisi’s first Australian film since his controversial take on the Azaria Chamberlain case–EVIL ANGELS (a.k.a. A CRY IN THE DARK) made in 1988. Schepisi has made a career of exploring very different genres of movies and it is therefore difficult to pin down a Schepisi style–despite his having worked with cinematographer Ian Baker on all but one of his eighteen films.

Although he directed THE DEVIL’S PLAYGROUND (1976) and THE CHANT OF JIMMY BLACKSMITH (1978) his name tends to be left off that prestigious list of directors of the 1970s who changed the face of Australian Cinema: Weir, Armstrong, Beresford and Campion. Yet many would argue his was an important voice in that creative resurgence. Among his other achievements are BARBAROSA (1982), PLENTY (1985), SIX DEGREES OF SEPARATION (1993) and LAST ORDERS (2001).

His choices keep his audience guessing, so in some sense it’s no surprise that he has decided to make a feature based on a novel by Australian Nobel Laureate the late Patrick White. White’s novels are beautifully written works that don’t provide easy entertainment. They can be emotionally dense, tough and judgemental pieces of literature. They are a challenge to read and are therefore a challenge to translate into cinematic drama. The characters are complex constructions and are extremely flawed, so finding relatable characters for an audience to engage with is yet another challenge for the White adaptor.

Screenwriter Judy Morris has done an excellent job of transforming White’s prose into a filmable script. Previously Morris was part of the team that wrote BABE: PIG IN THE CITY (1998) and HAPPY FEET (2006). EYE OF THE STORM is her first sole credit on a feature. Schepisi wanted Morris because she knew White personally and was acquainted with the Sydney theatre scene of the 1970s. Rush’s Basil is part of that world and we get glimpses of him partying with his old actor friends and colleagues. Morris is a veteran Australian actress with credits going back to the 1950s when she was a child.

The emotional action of the film lies in the spiky triangular relationship between siblings Dorothy and Basil and their mother Elizabeth. Both the adult children are effectively in hiding from their domineering mother, even now she is on her deathbed. Basil is Elizabeth’s favourite, but he remains emotionally distant from her. Dorothy doesn’t even know how to be in the same room as her mother. Their flashback scenes make it clear that when she was younger, Elizabeth Hunter was the sort of woman who competed with her daughter for male attention.

The other players in this tale are Elizabeth Hunter’s staff; the nurses who care for her around the clock and her cook. The family lawyer is in constant attendance waiting for a decision from the old woman about the final form of her Last Will and Testament.There is much awkward emotion and unspoken animosity between the family members. This difficult territory is where the film excels. This is not a story about an easy exit; it concerns people who are still trying to work out how they fit together even at the literal last moments.

Schepisi has assembled a fine cast. Although Rush and Davis are good as expected, Rampling shines as the glittering monster at the centre of the story. Elizabeth Hunter is on her way out, but we are shown many signs of her former glory. John Gaden plays the family lawyer with understated style and Robyn Nevin plays his wife. She and Rampling have a great scene together. Helen Morse plays Lotte the cook who has survived the Holocaust. Colin Friels has an amusing cameo as a Bob Hawke-like Prime Minister. The director’s daughter Alexandra Schepisi plays one of the day-nurses and does a beautiful job with her supporting role.

EYE OF THE STORM is a film of moments rather than a big narrative that pays off with a neat conclusion. If you accept the emotional untidiness of these lives as a normal part of the human condition, then there is much to enjoy here. This film will engage audience members who have had to deal with an ailing older relative and all the attendant history and emotion that this situation brings.

EYE OF THE STORM is in Australian cinemas now. It runs for 119 minutes. I rated it 3/5.