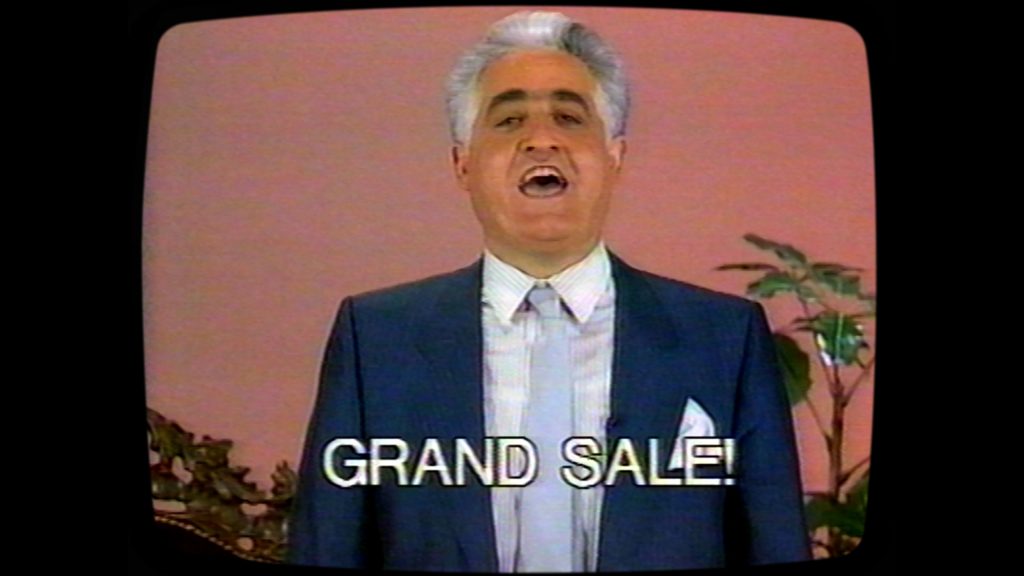

Palazzo Di Cozzo offers a glimpse at the rise and current plight of larger than life Melbourne furniture icon Franco Cozzo in the directorial debut from Madeleine Martiniello. We delve into Cozzo’s backstory, from his journey to Australia from Sicily (“32 days of shipping – it was too long”) to his ingenious ‘Grand Sale’ commercials in the 80s, to the waning interest from the public in baroque furniture. It was a sad inevitability, for as he puts it, all his Italian customers are in the cemetery. The documentary treats his furniture with reverence for what it represented to a large community of people seeking a better life – a reminder of home, and proof that they had achieved ‘the dream’. As a lover of antique furniture that borders on gaudy, I was completely charmed by this film.

Melburnians will likely be familiar with Cozzo but as a sheltered Perthian I had expectations verging on Versace. We open on Cozzo dousing himself in three different colognes – similar to the amount that those older ladies at Myer like to spray in your face without consent. He is getting ready to meet an important client – a woman who lives in the suburbs in a modest brick mansion and reminds me of every single one of my dear departed Pop’s female friends. Cozzo turns up at her house in a hot pink Audi driven by his second wife and colleague, waltzing into the room touting his own catchphrase – a true god of self-promotion. The client is contemplating spending $50,000 on a white baroque dining table and more furniture for the ‘gold’ room. “I might get more gold on this one too” she says, and I’ve found my inspiration for who I want to be when I grow up.

Martiniello lets talk show host Don Lane introduce Franco Cozzo’s backstory in footage from 1981. A younger Cozzo, who can by his own admission barely speak English, tells the audience how he started his business as a migrant living in burgeoning Melbourne in the 50s. Among the many door slams he received as an Italian door-to-door salesman who couldn’t speak’a the language, he had to get creative. He looked for the white houses (the Italians) and the blue houses (the Maltese) and the pink houses (the Greeks) and failing that, he would look for the basil and tomato plants in the front gardens. Cozzo found his first customers just by looking around and targeting migrants like himself who would appreciate someone who spoke their language, having the ingenuity later to present his commercials in English, Italian and Greek. Lane’s English-speaking audience laughs at his foreign eccentricities but he doesn’t care – in fact, he seems to get off on it. It’s a very clever way for audiences who may not be familiar with Cozzo to get an idea of his iconicity and appeal.

Music and performance play a big part in Cozzo’s life. Archival footage introduces us to Carosello – a musical variety show produced by Cozzo featuring Italian acts and ingeniously surrounded by his own commercials. He wanted to be a singer or a performer from a young age, alas he “had a very tough Daddy so I can no do that”. His daughter Gisella appears in interviews (she is child number four of his first family), winning Young Talent Time in 1984 and still involved in the music industry today. Cozzo even had a song written about him by fellow Melbourne Italian Tony Cursio, making it into the minor leagues of pop culture – forgotten by most but cherished by some (a bit like Luigi from WA Salvage.)

Papa Cozzo perhaps having a sale

But beneath the bravado and the catchphrases is a man who just wanted to please his Mama. Themes of motherly attachment come up several times, in Cozzo’s own narration of missing his mother after leaving Sicily, and eventually bringing her over to Australia. He had only one sister in Italy who tragically passed at a very young age and he promised his mother that if he ever married, he would have ‘a soccer team.’ From his two marriages Cozzo has nine daughters and one son – none of whom are interested in taking over the business. His mother helped raise his daughters from his first marriage, and an incredibly touching scene sees him visit her beautifully elaborate grave and tell Martiniello that he just wants his mother back.

My favourite scene of the film doesn’t actually feature Cozzo at all; rather, the impact his business had on fellow migrants. Vincent Lamberti’s precise cinematography tracks through the house of the Di Natale family, revealing gorgeous pastel pink fabrics and intricately designed baroque frames of the family’s impressive collection. Almost like a look through a dollhouse we see the furniture undisturbed by humans or pets, arranged in aesthetic scenes that hint at these pieces very much being a display of taste and success. Martiniello interviews the adult children of the furniture’s owners who have sadly passed. Their daughter tearfully reveals that she and her brother found Franco Cozzo receipts from 1976 that total $17,000 (for reference, a car was about $3000 the same year.) The idea that her working class parents would save and save to spend so much money on furniture broke her heart. Such symbols of status and culture were very important at the time since so many migrants came to Australia under the promise that they would earn more, quicker. Rather than thinking of them as the gaudy couches their elderly parents liked to show off, the furniture has taken on a whole new level of sentimentality in their heirs.

There’s a sadness lingering in the fact that the demand for this style of furniture has been on the decline for some time, existing now mostly in other foreigners and a few older, wealthy fans of Cozzo’s who buy perhaps for the novelty or the prestige. The pieces he sources are all handmade in Italy, making them too expensive for younger generations – especially those who don’t have a sentimental attachment to the Old country. All good things come to an end but while he was on top, Franco Cozzo’s reign was pretty fabulous.

Sitting through Palazzo Di Cozzo on a Sunday afternoon with a gin and tonic in hand was a delightful way to round out the weekend. Few films lately have left me feeling as cheery (and inspired to search for antique armchairs on Marketplace) and I feel privileged to have been let into a part of vintage Melbourne history that I otherwise would’ve missed. It’s an encouraging debut from Martiniello (who also wrote the film) and an affectionate account of an icon who most definitely achieved ‘the dream’. 7.5/10.

Palazzo Di Cozzo is in cinemas Thursday 16th September and if you go to the Opening Night screening at Luna Leederville/SX you get ciabatta and cheese. Bellissimo!